Though pretty much everything we write can use a fresh paint job every now and then, we need to stop somewhere. And the better we get at writing, the less time it takes to get to that stopping point.

Fortunately for us, there are tons of tools designed to help us improve. Here are three that I’ve found especially helpful:

Hemingway App

Though I only recently discovered Hemingway App, I’ve used it extensively. In fact, I’m using it to review this blog.

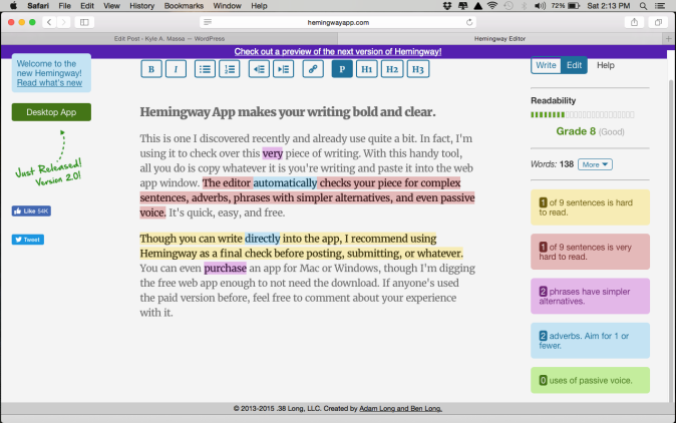

Just copy your writing and paste it into the Hemingway window. The app crawls your piece for complex sentences, adverbs, phrases with simpler alternatives, and even passive voice. As an example, here’s an early draft of this blog:

The highlights illustrate exactly where your readers might stumble over your writing. The app even recommends more precise words to try in place of complex ones.

And the best part? The Hemingway web app is free.

Trello

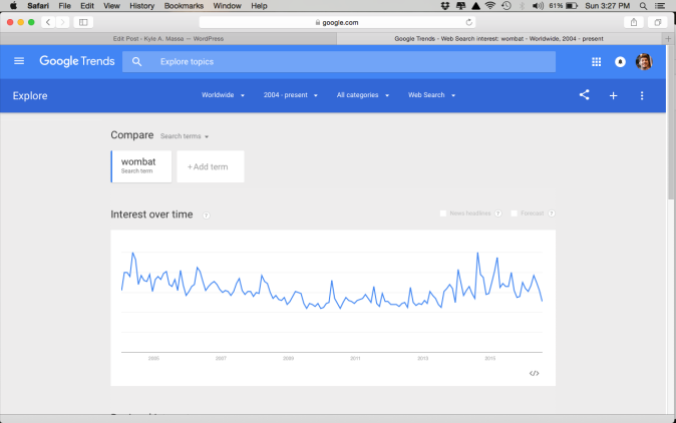

As soon as I saw this, I knew I would like Trello…

The truth is out there.

Anyway, there’s way more to this app than just good humor. It’s free to create an account and easy to get started.

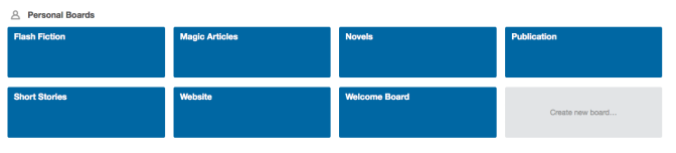

Once you’ve logged in, start by creating your boards. These might be general topics, projects you’re working on, specific mediums you write in, anything like that. Trello’s cool because it’s so open ended.

As you can see, I’ve divided my boards up into different forms of writing. Once you’ve set yours up, click on any board to add your projects.

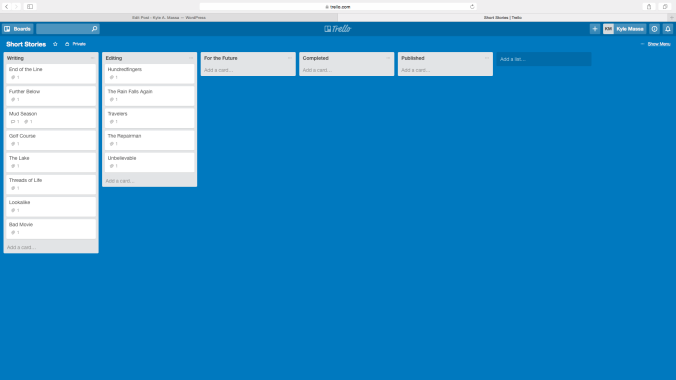

Within my short fiction board, each white card represents a different story. I attach my project files to each card so I can access them at any time. Plus, doing so provides a backup of my work in case my hard drive crashes (please don’t let that happen, universe).

The card structure also allows you to track your notes on every project, as I’ve done in the above screenshot. I find it’s the best way to keep my writing organized.

Scrivener

I’ve written about this one before, but I think it’s worth another look. Put simply, Scrivener is the perfect tool for novel writers.

I’ve written manuscripts on Microsoft Word, and though it works, I don’t think it’s the best option. With Word, it’s difficult to get an overview of your piece without scrolling through every page. If I want to change the sequence of the chapters, it’s a real pain to copy and paste thousands of words at a time. And for ancillary stuff like character bios, I have to create new documents in other windows.

In short, Word is fine, but it’s not designed for writing novels.

Scrivener is. It puts everything your novel needs in one place.

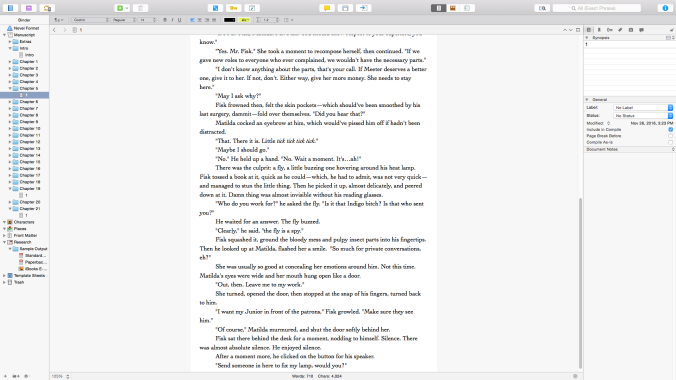

You’ve got your main workspace in the middle and a whole lot of other stuff surrounding it. The folders on the left represent your chapters. You can divide them into smaller sections or group them within different parts. You can also add character bios, setting descriptions, and even web pages with relevant information.

When you’re ready for feedback, you can export your piece into a ton of different file formats, including Word, Pages, .pdf, .mobi, and more. That’s right—Scrivener lets you make e-books with ease. If that doesn’t sound like a big deal to you, ask any indie author what it’s like trying to format an e-book. It’s a pain, and Scrivener makes it easy.

What Tools Do You Use?

Let me know in the comments. There are tons out there and I’m always looking for more!

Novels are cool, but they’re tough to write.

Novels are cool, but they’re tough to write.

For example, let’s say you’re writing a conversation between two characters. We’ll call them Roscoe and Winifred, because those names are fun to say.

For example, let’s say you’re writing a conversation between two characters. We’ll call them Roscoe and Winifred, because those names are fun to say.