The Babadook is not your average horror film.

There’s no gratuitous violence. There aren’t any jump-out scares. No blood. And–thank god–there are no dumb teenagers.

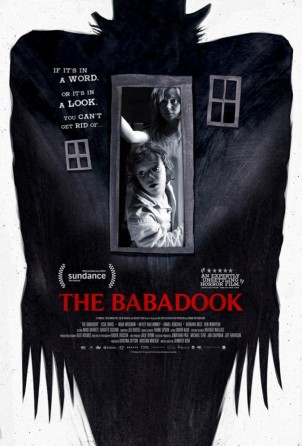

The Babadook is the story of Amelia Vannick (played by Essie Davis), a widow who lives alone with her troubled son, Samuel (Noah Wiseman). Amelia’s husband died on the same day her son was born, and neither of them have been quite right since. One night, Amelia finds a creepy book in her son’s room called Mister Babadook. The horror begins when the creature from the book stalks the family.

It might not sound all that scary from my description, but, trust me, The Babadook will frighten even the most experienced horror junkies. So what does this film do so well?

In a word: juxtaposition.

The Babadook pairs reality with fantasy, depression with home invasion, and suppression with the supernatural. Despite the poster and the synopsis, this film is as much about loss as it is about a monster.

Take writer/director Jennifer Kent’s interpretation of her own film, for instance: “Now, I’m not saying we all want to go and kill our kids, but a lot of women struggle. And it is a very taboo subject, to say that motherhood is anything but a perfect experience for women.”

It certainly isn’t for our main character, Amelia. Her husband died, she works at a job where she’s surrounded by death (a nursing home), and her son Samuel builds homemade weapons in the basement like a troubled little MacGyver. We can tell right from the beginning that the stress wears on her–and that much of her frustration is directed at Samuel.

As the film progresses and the Babadook invades the home, we see Amelia’s aggression heighten. The Babadook, in this case, represents Amelia’s suppressed anger; it’s no coincidence that it chooses to possess her and not her son. You’ve probably seen the moment from the trailer when Samuel shouts over and over, “Don’t let it in!” But his mother lets the Babadook–her anger–take full control, and that’s when things get even worse.

That is the power of fantasy. The Babadook is the personification of Amelia’s negative emotion, and a good one at that; if suppressed anger had a corporeal form, I’d imagine it wouldn’t be too pretty. Amelia sees the Babadook everywhere–in her home, at the police station, in her neighbor’s home. Here, writer/director Jennifer Kent gives us an important clue through the use of fantasy: Amelia can’t escape her negative emotions, no matter where she goes.

One of the coolest parts of the film is the use of montage. Not the kind of montage you see in a romantic comedy–I’m talking Russian filmmaker Sergei Eisenstein’s theory of film montage. Basically, the idea is that if you constantly show two images together in sequence, you can give both images a new, greater meaning. For example, if you show an image of a crying baby followed by an image of the grim reaper, you’ve given greater meaning to both images: you’re indicating that that baby might die, or you’re showing the passage of life, from the cradle to the grave.

Montage is a type of juxtaposition, and Kent uses it extensively with the Babadook and Amelia’s depression. We often see images of Amelia and the Babadook mirrored–Amelia holds a steak knife and the Babadook has knifelike fingers, for instance. Eventually, the real image and the fantastical one combine, and both transcend their original meaning: they represent a mother’s wish to kill her son.

The ending, to me, is the most intriguing part of the whole film. Amelia confronts the Babadook, and in doing so, she confronts the anger she feels toward her son and the depression she feels regarding her husband’s death. But, interestingly enough, that doesn’t actually kill the creature. The Babadook lives in the basement, chained up and weakened, but still alive. Amelia goes down to feed it, and the film ends.

What does this mean? Well, it’s certainly not the sort of happy ending we might expect. If we look back to classic works of horror, we see the recurring use of the subterranean to represent the subconscious (Lovecraft and Poe use this form of symbolism a fair bit). When you see people going down into the earth, it’s as if they’re traveling to a suppressed, secret part of the psyche.

Amelia’s basement serves the same role–she hides her negative emotions down in her subconscious mind, where they can’t hurt her or her son any more. For a while, at least…

You don’t need violence and blood to be frightening, and I think The Babadook proves that beyond a doubt. In this age of senseless violence and gratuitous gore, I was very happy to find a film that focuses on psychology rather than shock value. Writer/director Jennifer Kent uses fantasy to frighten us in a way that reality never could.

So if you decide to watch, I suggest doing it on a weekend. You probably won’t be getting any sleep.

Like creepy stories? You might enjoy horror story “Sightings.” It’s about a reporter tracking an angelic creature that brings with it a mysterious plague.